With Nostos, which features his beguiling landscapes delicately printed upon Grecian marble, Prince Nikolaos of Greece and Denmark explores poignant themes of homecoming, longing, as well as cultural and personal identity.

Trip: Prince Nikolaos, how did you discover your passion for the photographic medium? I read on your website that you’ve been doing it all your life but that you began professionally in 2013.

Prince Nikolaos: That is true. I used to do it as a hobby or as an amateur, particularly when I was a teenager, but then I weaned off it. Many years later, I was given a camera, and I started taking shots here and there. In the meantime, I worked in New York as a P.A. for WYW Channel 5. I got a lot of inspiration from my uncle in Spain, who used to do a lot of photography. My composition, I think — I’ve realized since — was probably part of looking very intently at the imagery that was taken by the camera crews who used to go out. I used to sit in the editing booth and do a lot of editing. That composition probably steered me in the right direction, unbeknownst to me then. I’ve always been aesthetically inclined. I love beautiful imagery, and beautiful art. I know that sounds a bit banal, but I’ve been interested in things that are looking just right.

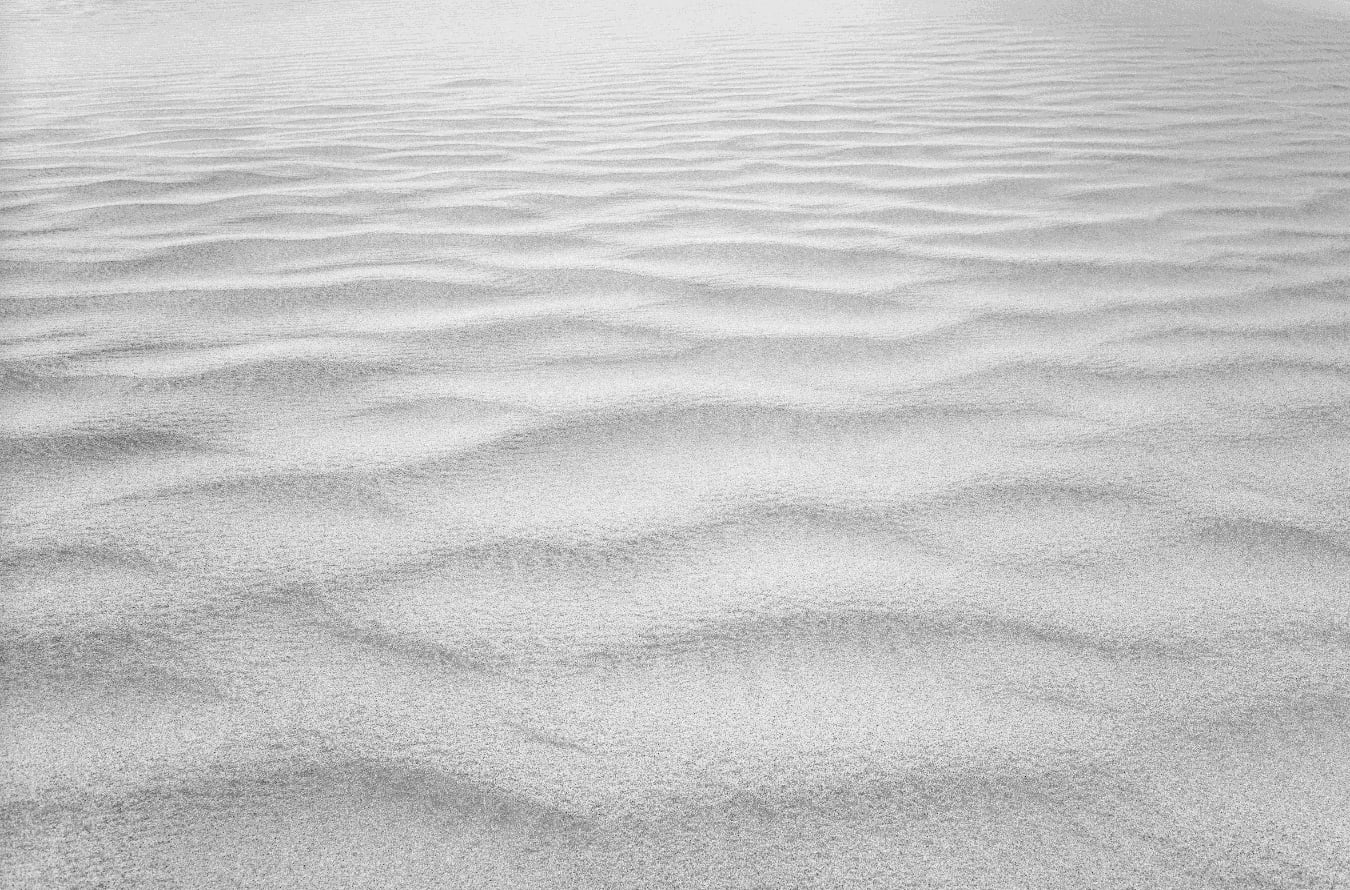

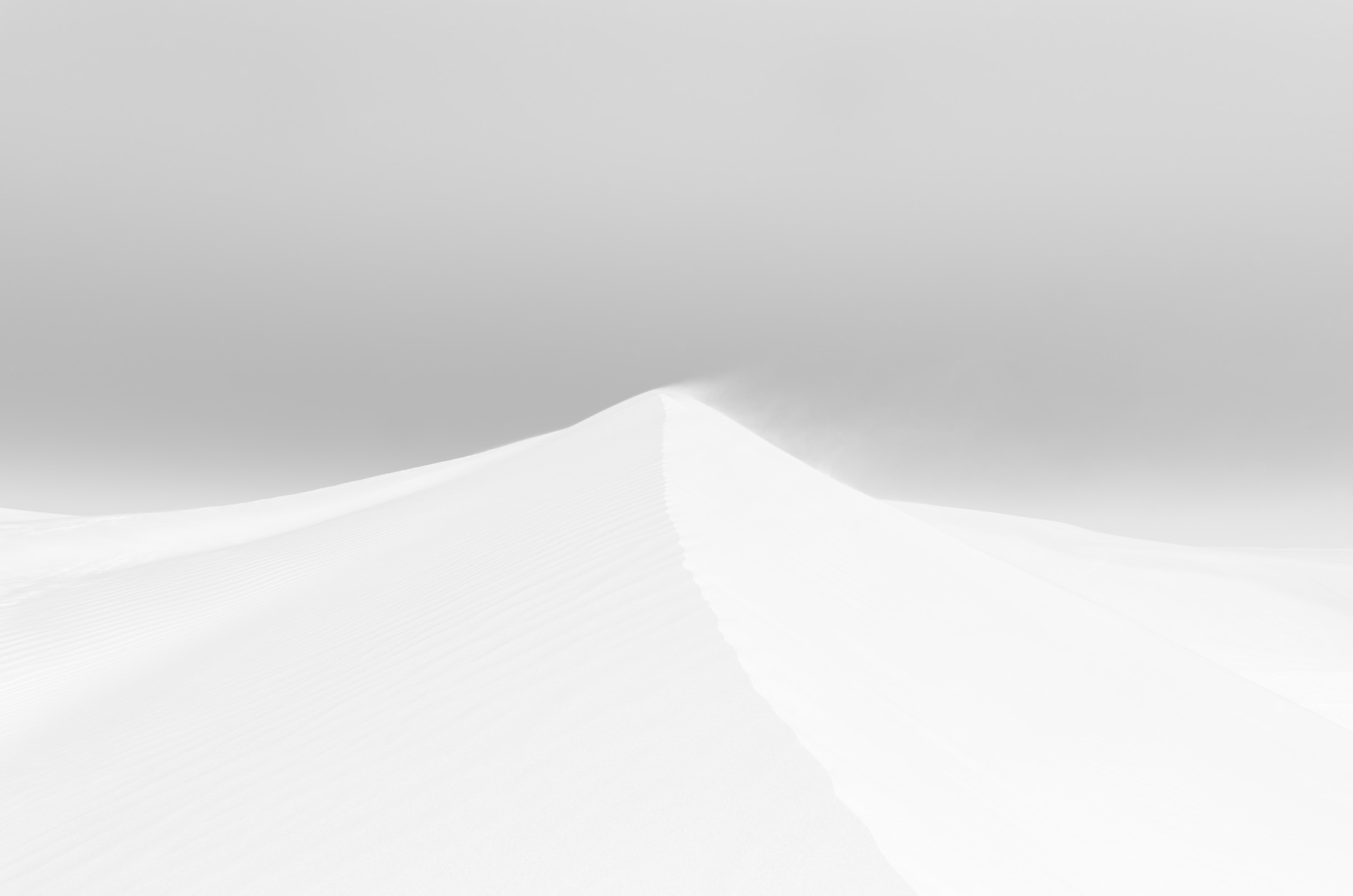

I then went out one day into the desert in Arizona, trying to capture the vast majesty of the spectacle. I was getting very frustrated until I was told: “Stop looking at the big picture and try to capture the feeling you are getting in your soul.” That changed everything. There is an ancient Greek word that describes that particular notion: Methexis. They call it ‘methe’ when you are drunk or high on what you are seeing. It can be used to describe the feeling you are getting from what you’re seeing and that the feeling you have inside your soul is what you are seeing. It goes both ways. That was something, though, I realized later. On a vanilla level, it was all about trying to capture what I was seeing, which I thought was fantastic.

Trip: That makes sense; every artistic journey is exactly that — a journey — and you learn new things as you go along and grow in your craft.

Prince Nikolaos: Precisely that. When I moved to Greece, the landscape, the sky, and the sea were so beautiful that I kept taking photographs. Somebody said: “This looks really good,” and — I hate to say — I said to myself, “I think so too, but does it work?” So I went and showed it to a couple of people in the industry, and they said: “You are on the right track, but you have to figure out” — and this was very good advice — “whether you are doing this because you’re enjoying it or do you want to dedicate yourself to it?” They expressed that it was important that you dedicate all your time to doing this; you can’t go off and do another day job and do this on the side because no one is going to take you seriously.

HRH Prince Nikolaos, Methexisand, 2019, Marble. Courtesy of Ethan Cohen Gallery.

I actually wanted to hear that because I had done a whole array of jobs in my life in the past, but this is the one thing that is my passion. I really love it. It is a passion that came to me later in life than I would have liked, but I am grateful that it did come. It has opened my eyes to be able to pass on that message to young people that it doesn’t matter what your parents want you to do or what you think you ought to do. Follow your passion, and even if you haven’t found it, one day, you might. Don’t be afraid of changing tack.

Trip: Your method of printing your photographs directly onto Grecian marble creates an ethereal, delicately textured effect, which I found especially affecting in Elusive Summit. What inspired this aesthetic and compositional decision? I can’t really think of any other photographers who do this!

Prince Nikolaos: As far as I know, nobody does, but it came about because the majority of my work leading up to that was landscapes of Greece. I was thinking to myself — I guess I’m a hopeless romantic — that it would be nice to print on a Greek surface. Originally I was thinking wood: “What’s a nice white wood?” I was thinking of birch. Yes, it grows here, but it was planted; it’s not indigenous to the country. Then, it suddenly dawned on me that we have the whitest marble in the world, which doesn’t have the watermarks and distortions. So I went to my printer and said: “You say you can print on anything; can you print on marble?” He said he didn’t know, but if you bring a piece of marble that is thin enough, we can try it. We did, and it didn’t work, but we were onto something.

Over time, we were able to fine-tune the technique, and the end result — as I’m glad to hear from you — is kind of fun! The interesting thing is the majority of the work that I do on marble is very heavily based on the color white. The reason that I do that is because the original marble is white, and therefore, I instruct the printer that if it reads anything white in the image, don’t print it. So anything that is white in the image is the actual marble coming through.

HRH Prince Nikolaos, Kisawa, 2023, Coffee Table (marble, bronze, glass). Courtesy of Ethan Cohen Gallery.

Trip: It’s a beautiful effect. It is a union between your work and the naturally occurring substance. When I was looking at some of the tables [featuring the imagery at Ethan Cohen Gallery] — as you said, the marble itself is unblemished, but by putting your photographs on it, especially those that depict eroding landscapes, it almost looks like that is a natural part of the marble’s composition. You have to look very closely to see that it has been laid onto it — a sort of fun trompe l’oeil.

Prince Nikolaos: With the large coffee table, I was surprised when I saw the first sample we did; it looked like it was carved out, and many people think it is. It is the nature of trial and error. Sometimes I’m looking for an effect, and I don’t achieve it; other times, I’m looking for a different effect, and I get a much better one. This is an example of the latter.

Trip: What does Nostos mean to you on a personal level? How do you apply this concept to the landscapes you are photographing?

Prince Nikolaos: Nostos is a notion of longing and a concept of return. I lived most of my life outside of Greece. I had the same feeling as a lot of my compatriots who live abroad. We’re all over the world, and there is always this longing to return. I finally managed to return, and my desire and longing were deeply rooted in my childhood. Once I did return, I was elated. Then I decided one day to move to this country once it was possible for me to do so. It was my desire, so I took a chance, not knowing if it would actually work. Sometimes you show up, and you’re like, “Oh, I miss New York City or London,” but in fact, it was the complete contrary; I was not only happy, I was even happier than I was expecting.

There is a yin and yang that is reflected in my work; it’s not just looking through a viewfinder and taking a photograph. Sometimes it is — I won’t lie to you — but more often than not, it’s like meditation. It’s not true meditation because I’ve never been able to fine-tune that method, but it is the closest I’ve ever gotten. Everything else is washed out of my brain when I'm looking through the viewfinder. It is a fantastic feeling. When you’re looking through the viewfinder, you’ve got one eye closed; I’m just looking at everything the viewfinder sees. That’s one of the reasons I use traditional methods, though I know I’ll have to change that eventually. I like to look through a mirror — I use a DSLR — I hate to look and see a digital image coming back at me because it is not reality; it is an interpretation of reality, and it bugs me. I know I’m going to have to get over that. When I look through the viewfinder, I’m looking at my subject, and everything else is blacked out. Fantastic feeling.

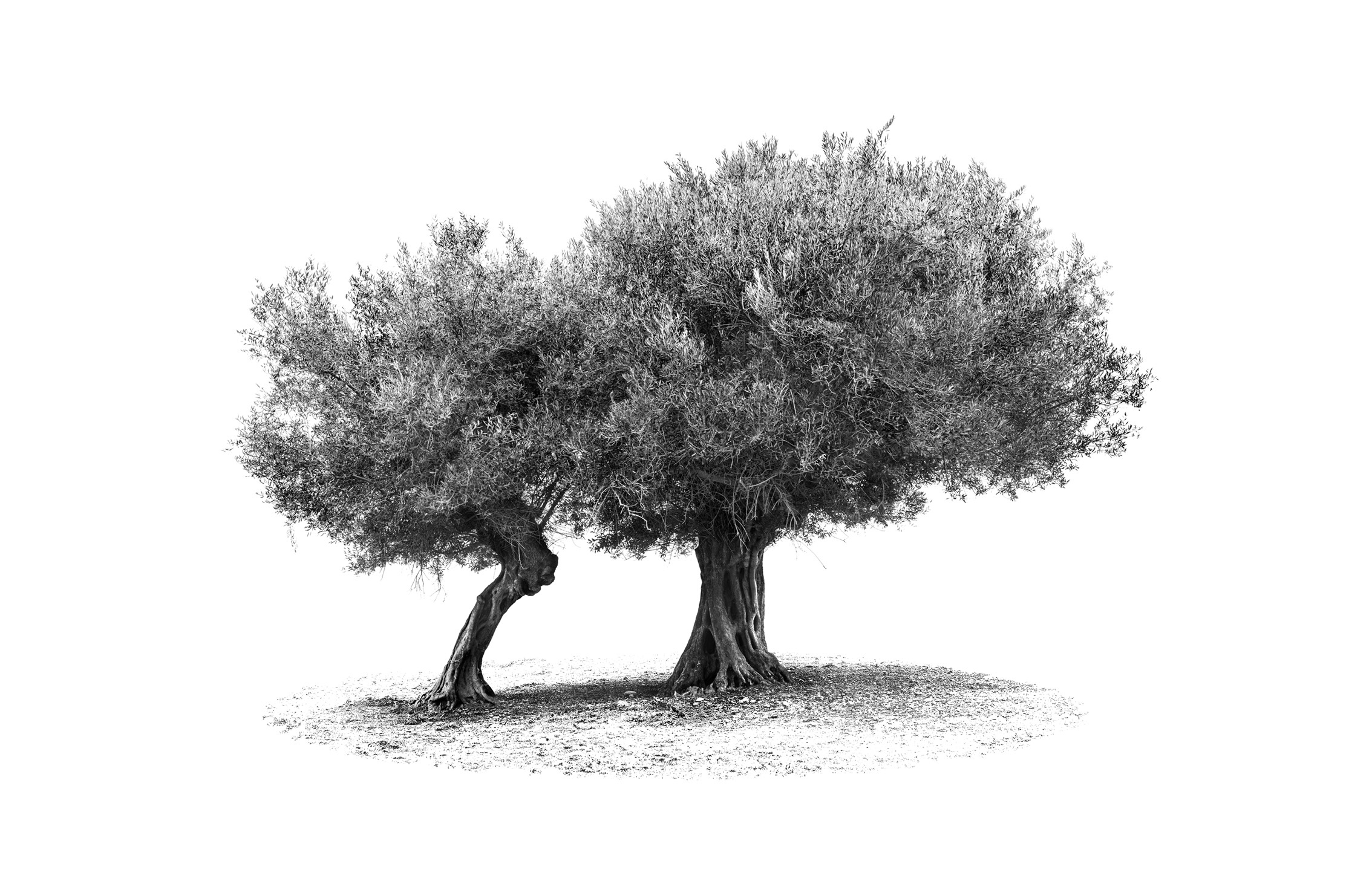

Trip: It creates a singularity; like you said, it is a lot like meditation. I noticed that in a lot of your photographs — like Together, for example — because the trees are solitary and the primary focus. It creates a singularity of mind that is peaceful and direct.

Prince Nikolaos: More often than not, I am absolutely alone when I am taking these photographs. On the particular occasion of that tree, I went to this property — these trees are not in an olive grove, which is wild — and I took a picture with my iPhone. I said to the guy who owned the property: “Do you mind if I spend a couple of days here taking photographs?” and he said, “Yeah, go ahead.” It was a very moving time. It was the middle of February, and it was cold, and you suddenly got this connection with this tree because you spent so much time with it. You start seeing different shapes and images coming through the leaves. That work of mine is one of my favorites. I feel I have a very spiritual connection to those trees.

HRH Prince Nikolaos,Together, 2024, Photography on paper on board. Courtesy of Ethan Cohen Gallery.

Trip: What inspired you to photograph those particular trees? How did they speak to you and the overarching concept of reconnecting with the land? They are quite alluring — there’s something almost anthropomorphic — the way the one looks sort of like a bent leg.

Prince Nikolaos: Everybody has a different interpretation. These two trees are sitting at the edge of a cliff. Behind them, in the distance, you see the sea and a tiny outcropping island. As you correctly pointed out, I took all that out, and I went low enough that you couldn’t see much of anything, just the sky behind you. You say that it looks like a leg; some people say that it looks like a horse’s head; sometimes it almost looked like a man and a woman — I saw the one tree on the right, which is larger, and the one on the left, which is smaller, coming towards the larger one — and it's almost like the woman is attracted to him, and he peers the other way and is like, “You’re going to have to try harder.”

Trip: I remember discussing at the gallery with my colleague — after being told how old these trees are — the thought of them being companions through time and history.

Prince Nikolaos: Absolutely — that’s a huge part of it. Imagine what these trees have seen and what’ve been through, but they’re still here. There are so many messages on so many different levels. These trees are intertwined in their branches up and above. With olive trees, the plumage that you see above is pretty much mirrored in the ground where the roots are. So these two trees — which we’ve discovered recently through science — communicate with each other through the roots. They communicated both above and below the ground.

There is a whole message there if you look at the ancient Greek times, with the real world and Hades underground, and these two trees are symbiotic in both. There is a huge message there and a message to remind us that these two beautiful trees have been there for hundreds and hundreds of years — they can live for over two thousand — if we are not careful with our environment, these beautiful things that have been here for so long and that provide us with fruits and olive oil and so on will cease.

Trip: It also feels symbolic of preserving Greek culture and what is important to you against outside forces.

Prince Nikolaos: It is a hundred percent true! That is even more so when I print on marble, which is ancient and Greek.

HRH Prince Nikolaos, Sounio, 2021, Triptych, paper on board. Courtesy of Ethan Cohen Gallery.

Trip: What personal or aesthetic criteria do you have for choosing a particular monument or landscape to photograph? Do you consider what will look best on the white marble?

Prince Nikolaos: For marble, it is very particular. I am looking at doing a black-and-white image, and in some cases, I will invert the image so what was black is white and vice versa, and I am thinking of that while I am taking the photograph. Oftentimes, though, it is fine to have that concept in your mind, but when you get back to the editing room, you realize that actually didn’t work. Equally, while I’m out there doing what I think is a photograph of a certain subject, out of the corner of my eye, I’ll see something that is completely different and think, “Oh! This is interesting.” Then the whole shoot shifts onto a different subject; that’s the very abstract stuff.

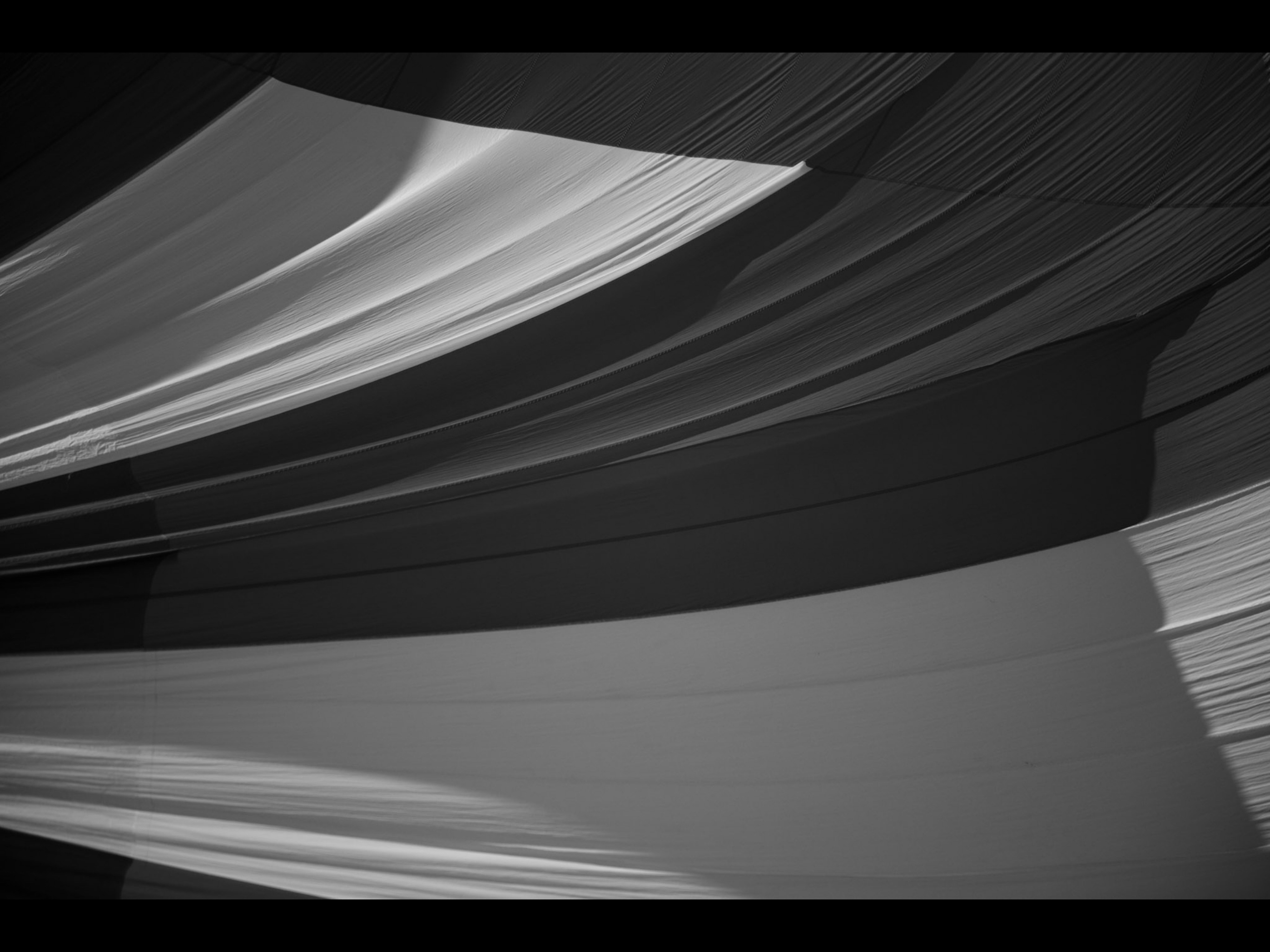

Trip: I’m particularly curious about Acropolis II, which you shot through water. Can you tell me a bit about the process behind that triptych?

Prince Nikolaos: So here’s what happened: I love water, and I love photographing water, the way it reflects the light and so forth. Then I had this idea — don’t ask me why it came to me — but since I sometimes print on aluminum, I had some aluminum panels of some photographs, and I said, “Why don’t I try to take a photograph through the sea.” So I went to the beach, dumped a panel with one of my photographs on it, and re-photographed it. Then I had this idea once I looked at the end result and decided I’d love to do a whole series of these. Soon after I found out that COVID was about to hit us with a lockdown, I rushed to my lab and asked them to print me eight pieces. When the lockdown did come, I actually had a very productive time.

HRH Prince Nikolaos, Acropolis II, 2024, Triptych, photography on paper on board. Courtesy of Ethan Cohen Gallery.

This process produced so many different results because you just get a slight distortion on a calm day with no wind. On a windy day, the light refracts on the surface of the water, resulting in a completely different image from the original. I love playing with formats. All these effects I could do with Photoshop, but I don’t like to use third-party mediums. I’ve said this before, but if you are patient enough and in the right place, nature will provide the colors and imagery you are looking for. Sometimes it may even surprise you and give you something completely different than you were expecting.

Trip: Right — and for lack of a better word — it’s rather trippy or psychedelic.

Prince Nikolaos: It’s very psychedelic. I called it Acropolis, but my brother said to me, “Call it Acid.”

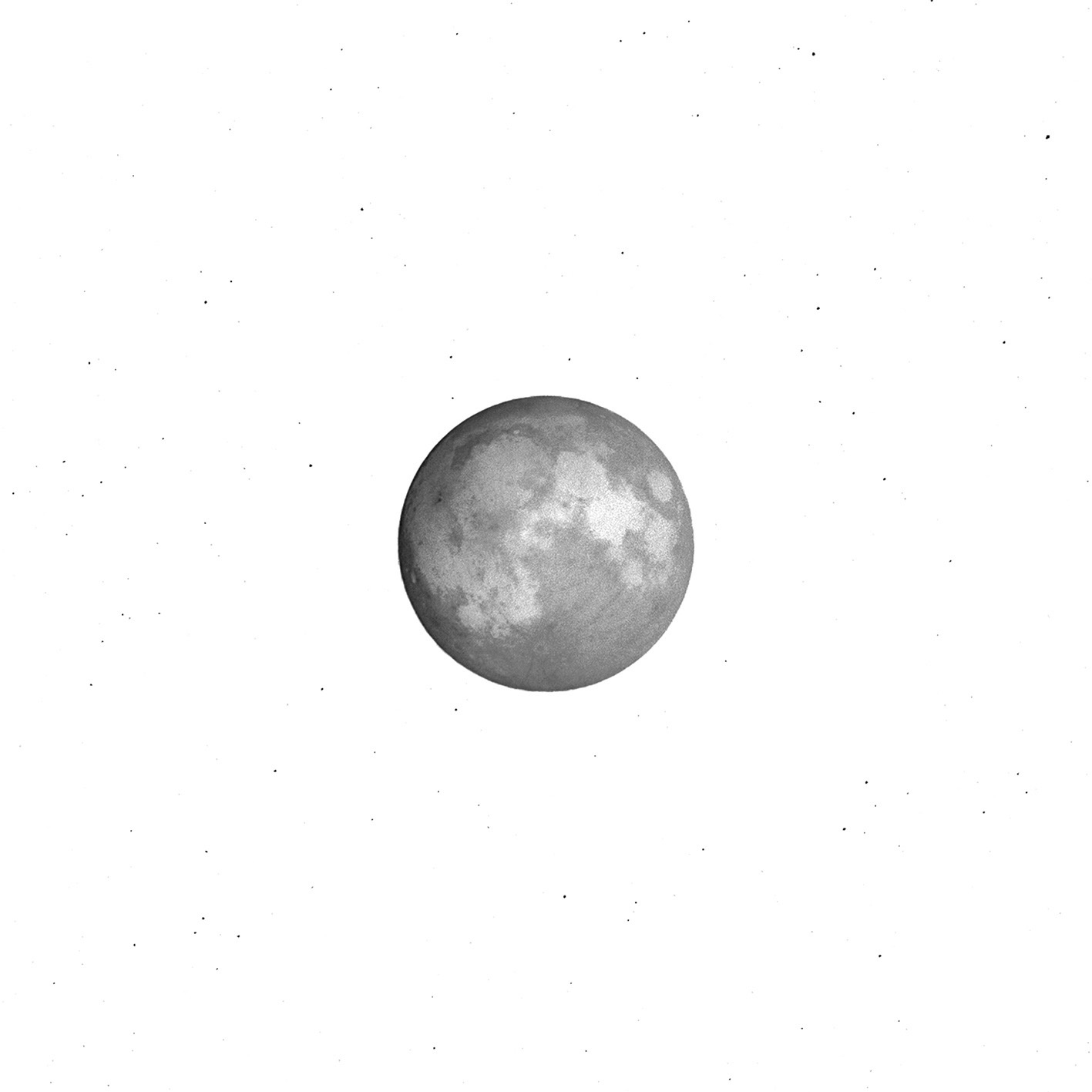

HRH Prince Nikolaos, Aweclipse, 2022, Side table, marble, bronze, glass. Courtesy of Ethan Cohen Gallery.

Trip: There’s a sense of revelry to it, like you’re looking at it drunk in the heat of the moment. This isn’t so much a question, but I was looking at the side table with the image of the eclipse on it, and when looking closely at it, what I thought were imperfections in the marble were actually stars and constellations.

Prince Nikolaos: I’m so glad you did that! That piece is one of the examples of where I took the black-and-white and inverted it so the black spots are stars. I’ve blown that image up before, and the detail of the stars and constellations is incredible. I love astronomy. I was curious, so I looked at the exact time and date, and I was able to find the constellations where I was located when I shot it. It was a lunar eclipse in 2017, and it was the first time I’d seen a full lunar eclipse, so because I was expecting it, I had my tripod on the roof of a building on one of the Greek islands. My friends and family were down below partying ‘at the moon’ with music and so on, and it’s another example of one the times when I’m up there alone, regardless of the music and the sound of everybody having a great time — which is lovely and wonderful — I blocked that all out, and I was just looking at what I was seeing. You know, sometimes, human beings — I don’t know if you’ve ever watched a solar eclipse — as soon as it happens, you hear everybody start to scream. Whooping and so forth. I was like, “Guys, enjoy the silence of this. It’s incredible.” That’s the feeling I get when I’m looking through the viewfinder. I could feel the silence even though there was music. I don’t want to sound like a hippie or anything, but I do feel a connection with nature. It’s a beautiful, beautiful feeling.

Trip: It is a personal connection with the moon, something larger than you. It’s humbling.

Prince Nikolaos: It was pure elation. When I came down when I was done, I felt like I had taken something even though I hadn’t.

Trip: You were high on the moon.

Prince Nikolaos: Ha! I was high on the moon.

HRH Prince Nikolaos, Elusive Summit, 2019, Marble. Courtesy of Ethan Cohen Gallery.

Trip: None of your photographs feature human subjects; instead, they capture the landscapes and monuments' solitary majesty. What was the artistic or thematic mindset behind the decision?

Prince Nikolaos: When I was a teenager, and I told you I would do a lot of photography, it was a hundred percent focused on humans. It was human portraits, candid portraits — in other words, I’d be far away with a telescopic lens and capture people in the natural moment, laughing, reading, talking to each other, just capturing people’s natural expressions, and I loved that. This was when I was in my teens, and they were usually my family, friends, and girlfriends. When I started picking up my camera again, and I would do the same thing, people started complaining: “Oh, that’s too many wrinkles. Can you fix that?” I was like, “You know what, no, that’s who you are. Live with it.”

I didn’t do it consciously, but when I went to Arizona, I had this epiphany where I was so drawn into nature that I sort of tongue-in-cheek said, “Now I take pictures of nature, which doesn’t complain about its imperfections.” The truth is that I like to portray nature in her natural beauty. I don’t know if I’m trying to teach a lesson, but every time I take a photograph, I’m trying to capture a moment that my eyes have seen, and I’d like to share it. That’s the raw bottom line of it. Nature has so much beauty to show us. We just need to stop and look. I’m just the messenger; the artist is nature.