Deininger, Osprey and Pray (side view)

I have seldom had the sense of picking up on new directions at a group art exhibition but so it was at Goodbye Horses in the humongous post-industrial space of the Ethan Cohen Gallery on West 17th Street. This show took its name from a 1988 song by Q Lazzarus, which got a cultish following when it was used for its eerie quality in The Silence of the Lambs, the 1991 movie which introduced the serial killer, Hannibal Lecter. The song’s repeated refrain is Goodbye horses/I’m going to fly over you.

Isaac Aden and Lara Birgit Kamhi, the curators of the show, were in part referencing the way an artist can fly over areas of apparently used-up territory and come up with something wholly singular, As when Nick van Woert sliced a figurative wooden statue into three in Anatomica and when he presents what seems to be a thickly pigmented canvas in Journey To The Surface (Party’s Over), but which proves, upon closer inspection to be a gnarly oblong of Norwegian pine bark.

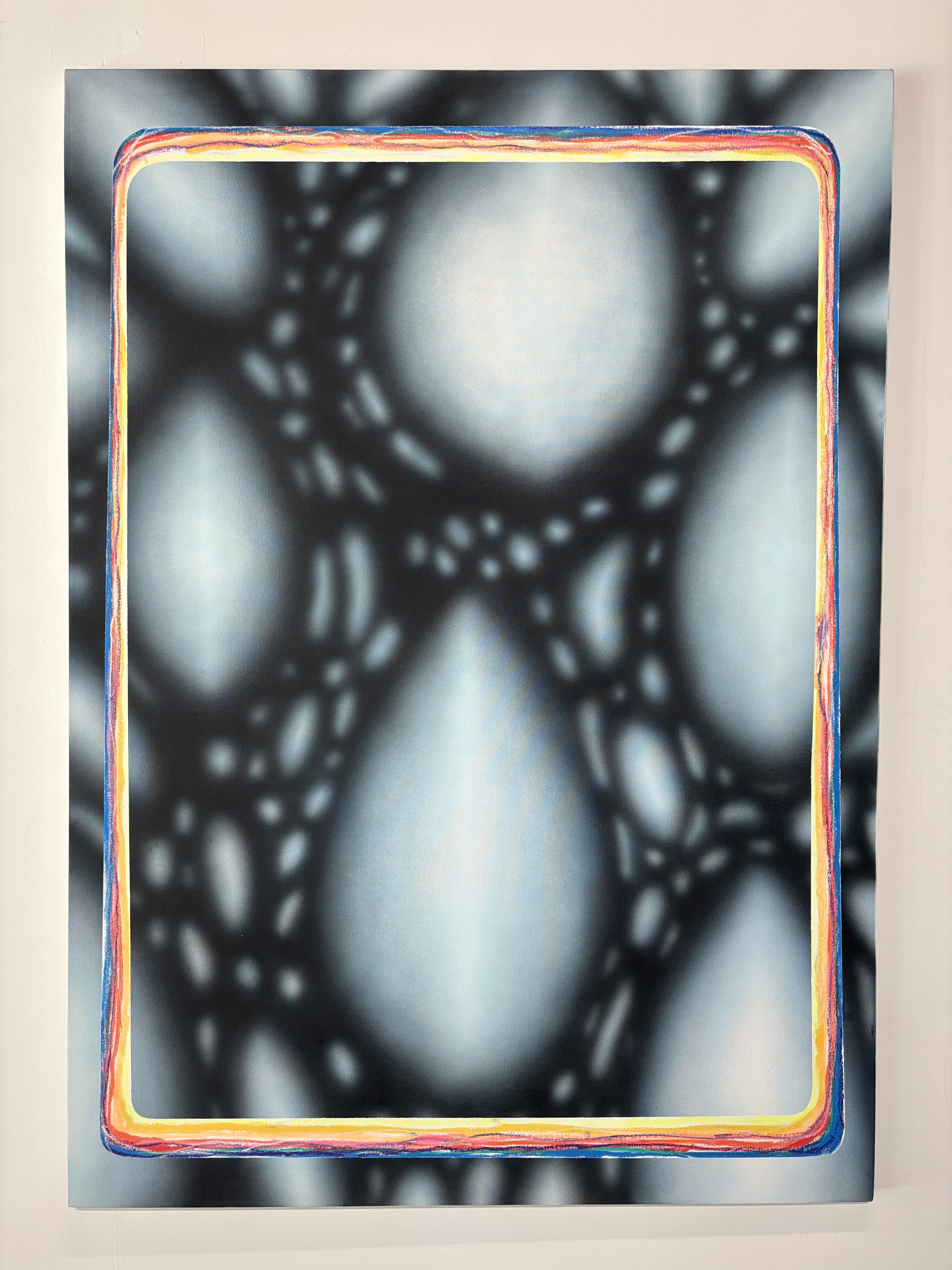

As to my sense of something new, that was provoked by the number of abstractions in the show that seemed to me to be loaded with meaning. This is hardly brand-new in itself. Willem de Kooning derived abstractions from landscape as did Elaine de Kooning from the human figure. Other eye-catchers at Ethan Cohen included a canvas that swept abstraction into becoming a real-world eyeful, Kabbalah by Erik Foss, which evokes branches, and another by Foss, Dreamwalkers, which seemed as meaningful as a sign.

“I’ve been in New York for thirty years so when I go back to Phoenix to visit my mom I’ll take photos,” Foss told me when I asked about this. “The last time I went out there I saw something in the sky that I took a photo of something in the sky. There was a lot of UFO action. And I think that’s what it was that I painted. Because it wasn’t planned what I painted.”

Eric Foss, Dreamwatchers

Osprey and Pray by Thomas Deininger was one of the eyecatchers in the show. Make that a startling double eyecatcher, full frontal and sidewise. Just look at the pix, and you’ll see the remarkable way he contrives to create utterly convincing artworks from throwaways, dumb found stuff. “It’s kind of a scavenger hunt” he says.

Deininger’s subject matter is the natural world. The desperately threatened natural world. “I’m a birdwatcher and I’ve always wanted to do an osprey,” he said. “The osprey is one of the few success stories of environmental intervention. They can be happy stories or sad stories. That one was kind of a celebration.”

It’s hard to accept that the frontal and side pictures of Osprey and Pray are of the same work but getting such acceptance is a crucial element in Deininger’s artmaking drive. “To be sure of ourselves feels good,” he said. “To get through the world you have to make judgement calls. It opens up the brain to new connections. Really the whole world is an illusion. It’s carefully constructed and agreed upon. At least politically these days.”

How long did making the piece take?

“I really don’t know,” he said. “Because I work in these bizarre fits. I usually don’t work from start to finish, I have two or three birds working at once.”

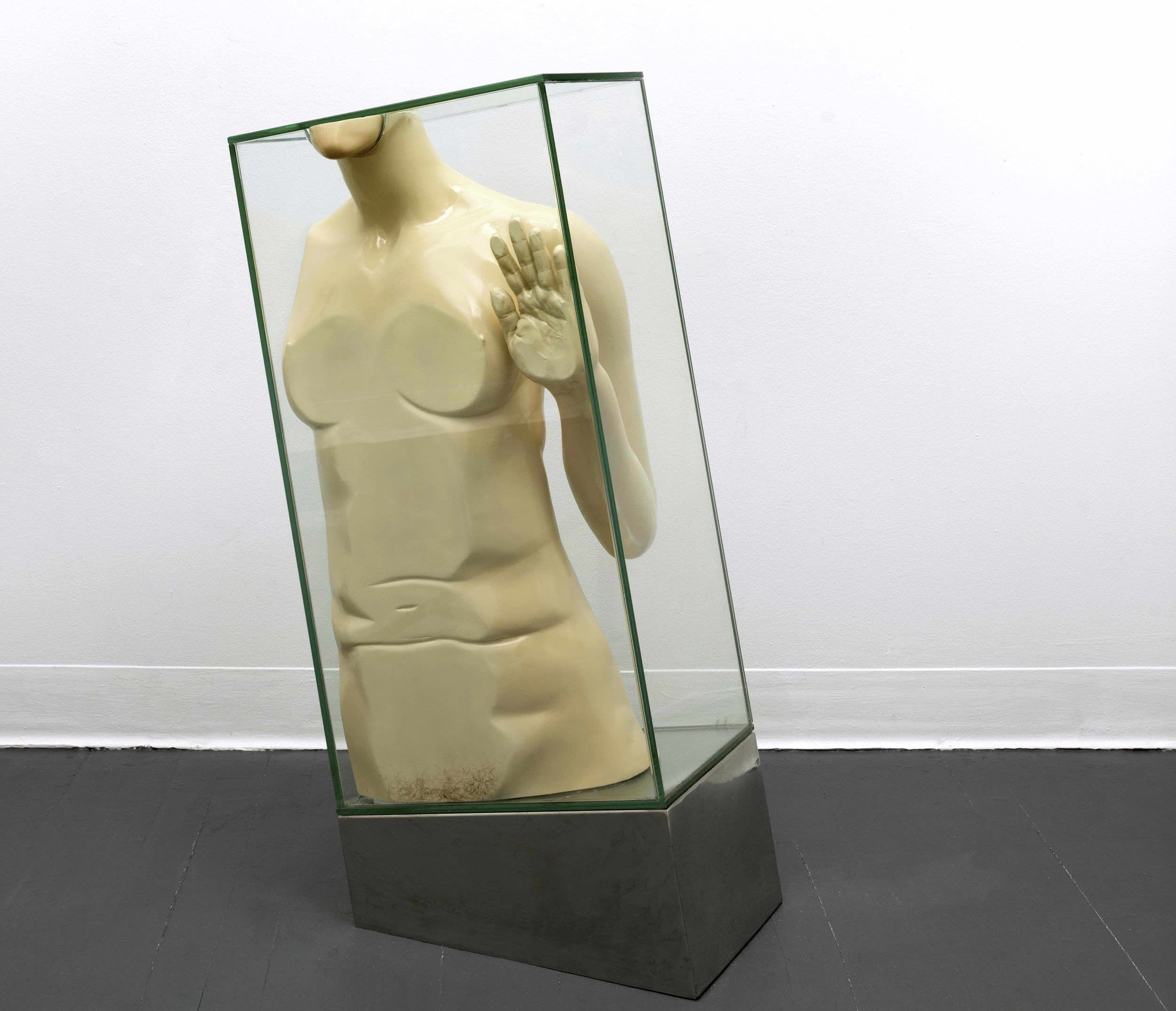

Nick van Woert

Yuli Aloni Primor wound up in the show because Ethan Cohen saw her sculptures in a show at Mana Contemporary, amongst them Madison, which features a female struggling against confinement in a seethru oblong, which wound up in a key position at the top of his stairs. Madison got its name, Primor told me, because the idea had budded as she walked on Madison Avenue with her supportive father. Much of Primor’s work deals with threat, vulnerability, but it was clear to me as we talked that the piece wasn’t about female oppression. So what was it about?

Yuli Aloni Primor, Madison, 2019, Fiberglass, glass, and metal, 88.9 x 38.1 x 25.4 cm, 35 x 15 x 10 in

“It’s about freedom,” she said. “I can imagine Madison the mannequin, crashing through the window. Kind of crashing through the glass ceiling also. Or the glass wall. I think Madison is very interesting in general. The human body is reduced to zero, When I expose Madison from the side you see a hollow shell. It’s a construction of identity. But at the end of the day it’s just fiberglass.”